Art Spiegelman’s CO-MIX: A Retrospective is an exhibition of gripping work, but comic books don’t necessarily translate to galleries

Pictures in an art gallery, by contrast, are almost invariably hung on walls, usually in positions amenable to the direct gaze of one or more standing viewers. The pictures can be united on the basis of painter, theme, subject matter, style and chronology. But unlike comics, storytelling – an adherence to a format of sequentiality – is not essential to their success.

Okay, this all seems pretty obvious. But what happens when you take comic-book art, with its simultaneous presentation of image, caption and word balloon organized in panels, and give it the art-gallery treatment? The answer is going to look pretty much like the exhibition Art Spiegelman’s CO-MIX: A Retrospective, now up at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. Originating in France in January, 2012, the show has, with some variations, been travelling pretty much constantly ever since, including a stay of almost four months last year at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Spiegelman is, of course, most famous for Maus, a two-volume phenomenon 13 years in the making that won him a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992, and almost single-handedly established the so-called “graphic novel” idiom. It’s a term he dislikes as much as Miles Davis disdained having his music called “jazz.”

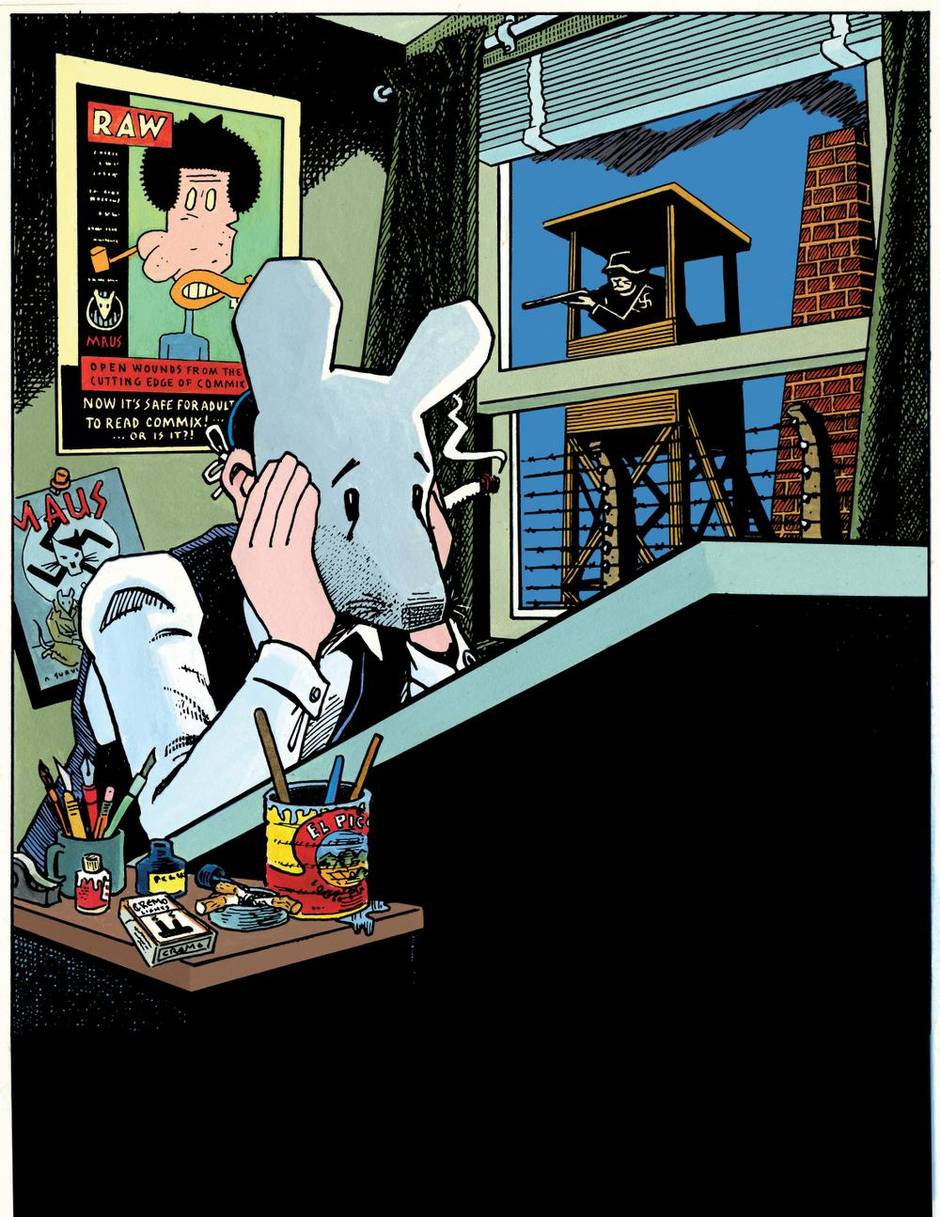

But whatever the nomenclature, Maus was and remains a towering achievement, one of the singular artistic works to come out of the 20th century. Part history, biography and autobiography, it has two narrative strands weaving past and present. One’s the recreation of the excruciating Nazi-era experiences of his Polish-born father, Vladek, a Holocaust survivor, as related by Vladek to his son in a series of taped interviews. The other thread traces the fraught relationships between Spiegelman, his difficult father and their tortured past (including the 1968 death, by suicide, of Spiegelman’s mother, Anja). In a brilliant, albeit controversial, feat of anthropomorphic allegory, Spiegelman draws his Jewish characters as mice (hence the books’ title), the Nazis as cats, French as frogs, Poles as pigs, and so on.

Clearly there was something happening here, something beyond the superheroes-in-tights fare of a lot of comic books and the chuckle-headed humour of the weekend funny papers. While much of Maus’s appeal came from its mass-entertainment trappings, there was also an artfulness in the seriousness and inventiveness of its presentation that makes the books seem like acts of personal necessity and individual expression. And when you’re talking like that, you’re talking high art, and when you’re talking high art, you’re talking about museums and galleries – places such as New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which, in 1991, duly assembled a show of Spiegelman’s preparatory and final drawings for Maus’s two volumes.

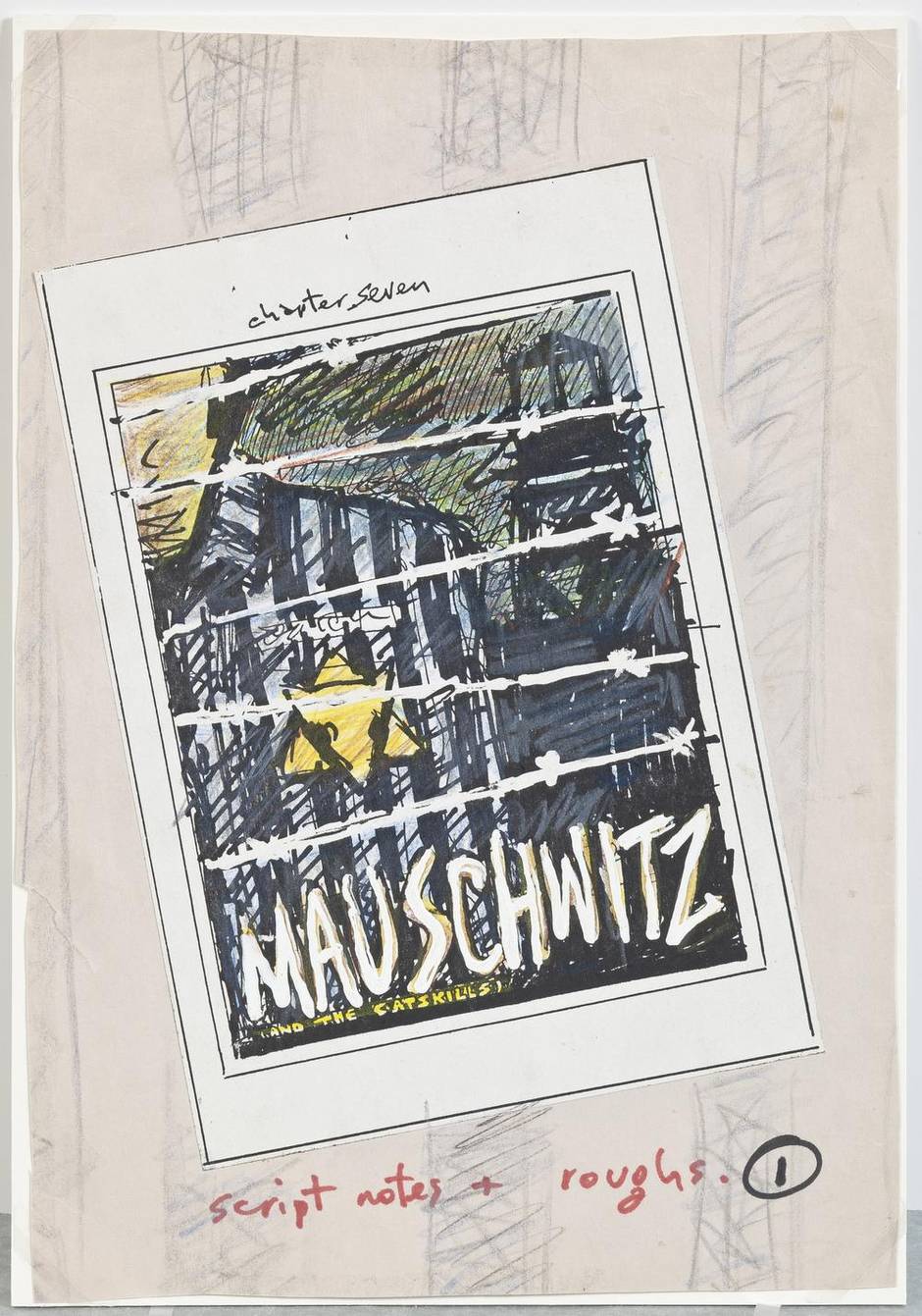

Unsurprisingly, Maus, while just one of 10 thematic zones or subject areas in the exhibition, takes up most of the real estate devoted to the AGO show, and it’s positioned pretty much at the exhibition’s midway point. The Maus zone includes memorabilia, reference material, preparatory work, finished illustrations and the like. But it’s dominated by two elements: a facsimile of the finished manuscript for Maus I from 1986, hung as an 8-by-18 image grid reminiscent of an Arnaud Maggs portrait multiple; and, across from it, a long, horizontal, page-by-page display of the actual 1991 manuscript for Maus II, A Survivor’s Tale: And Here My Troubles Began. It is “annotated” at certain junctures with preparatory sketches, and a speaker on the ceiling replays some of Spiegelman’s conversations with his father.

As physical fact and homage to Spiegelman’s herculean effort, these elements make an impressive sight. But as a gallery experience, they leave much to be desired. There’s simply too much text to read, too many drawings to pore over. If anything, the exhibition doesn’t elevate Maus’s stature as museum-worthy art so much as reinforce the notion that its first incarnation, as mass-produced artifact for sedentary consumption, was its best.

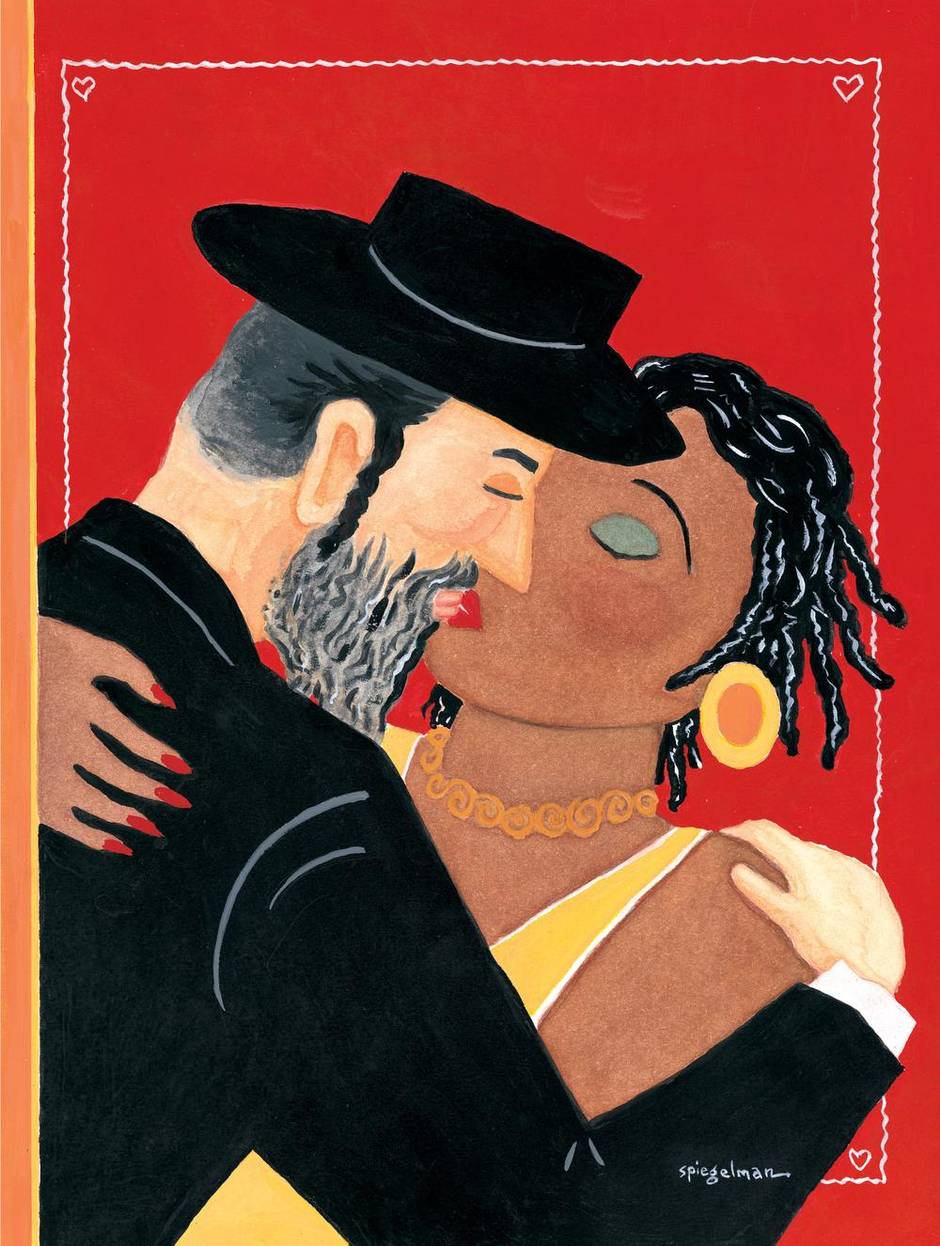

This sensation (and variations of it) hang over much of the rest of the exhibition. For instance, a zone devoted to the cover illustrations Spiegelman did for The New Yorker between 1992 and 2002 affirms their deserved fame, but the inclusion of the gouache-on-paper originals adds little to their “story.” (A revisit Friday to the show revealed dramatic improvements to the lighting. Done at the direction of the artist, they greatly enhance the visitor experience.)

This is art made foremost for industrial-scale reproduction. As a result, it’s often CO-MIX’s rough stuff – the preparatory sketches in marker and coloured pencil, ink and pastel, the text outlines, the outtakes, the scrawls in notebooks, the detritus of process – that’s most involving and most congruent with the protocols of gallery-going. (How much more interesting, too, if The New Yorker zone could present some of the Spiegelmans the magazine rejected, samples of which can be found on page 57 in the exhibition catalogue.)

For many, the exhibition’s high point likely will come early, in the spaces devoted to the artist’s pre-Maus output from the late 1960s and 1970s, when a young Spiegelman was a creative consultant for Topps Chewing Gum and drawing for such underground/alternative publications as The East Village Other, Arcade and Short Order Comix. A particularly heady example of the Spiegelman oeuvre at that time is Nervous Rex, The Malpractice Suite from 1977, a two-page collage-style lampoon of the then-popular Rex Morgan, M.D. newspaper comic strip, its subversiveness seemingly fuelled as much by the cartoonist’s LSD intake as his love of Surrealism and William S. Burroughs’s cut-ups.

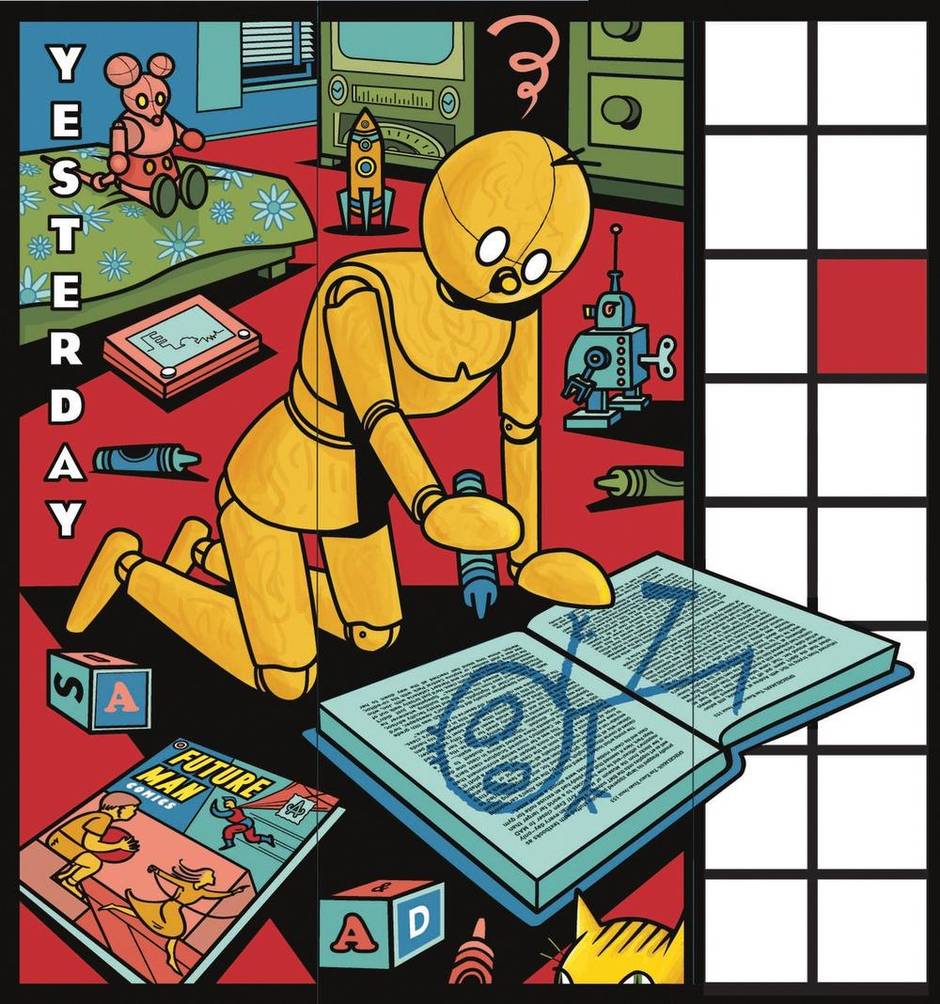

Post-Maus, Spiegelman has kept on keeping on, often producing striking work such as The New Yorker covers. He’s pushed, too, beyond the page, as happened in 2010 with Hapless Hooligan in “Still Moving,” an animation-and-stage collaboration with New York’s Pilobolus dance troupe. (A seven-minute video excerpt is screened at the AGO.) In 2012 he installed a large, painted-glass mural titled It Was Today, Only Yesterday in the cafeteria of his alma mater, New York’s High School of Art and Design.

Yet for all the power and variety of these newer works, they exist in the weighty shadow of Maus. It’s a burden Spiegelman, at 66, clearly feels. At a media conference earlier this week at the AGO, he spoke of its success as “the 500-pound mouse that’s been chasing me ever since,” of being “trapped in a machine I made.” In Europe, an artist tends to be held in perpetual esteem for his greatest work, regardless of what else he has produced, while in the United States, an artist is only as great as his next project. Listening to Spiegelman, you sensed (or maybe just imagined) that he’s either looking for or hoping to find the Anna Karenina to Maus’s War and Peace.

A couple of years ago, Robert Storr, the former MoMA curator who organized the 1991 Maus show, wrote of his hope that the widespread recognition of that work’s excellence and its cultural significance would result in an ever-crashing wave of museum exhibitions for other graphic novelists. He even imagined museums setting up their own comics departments. While it’s true museums have warmed to comic art – just a few yards from its Spiegelman showcase, the AGO is presenting 14 framed pages from Fatherland, a gripping, recently published graphic novel by Toronto’s Nina Bunjevac – it hasn’t been a total clasp to the bosom.

Perhaps the mixed results of the AGO show point to some inherent limitations in Storr’s vision. Perhaps comics are best appreciated as comics. And if there’s a place for their creators in a public gallery, might it not be in interdisciplinary or compare-and-contrast shows where Spiegelman is placed cheek by jowl with, say, Lynd Ward, Frans Masereel, Graham Gillmore, Al Jaffee and – oh, why not – Francisco Goya?

Art Spiegelman’s CO-MIX: A Retrospective opens Saturday at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto for a run ending March 15, 2015. Spiegelman appears Jan. 26, 2015, at Toronto’s Bloor Hot Docs Cinema to deliver a talk titled What the %@&*! Happened to Comics? Tickets: kofflerarts.org. Nina Bunjevac: Out of the Fatherland is at the AGO through midsummer 2015.