Last year, Lady Gaga released John Wayne, a rollicking song about wanting to be with a wild, cowboy-like man. The hectic music video looked like a trailer for a doomed-youth film by Quentin Tarantino, whose western feature, Django Unchained, came out in 2012.

Western stories are a minor genre these days, but as Gaga and Tarantino have shown, the mystique of the spur and the frontier remains strong. An ambitious new exhibition at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts looks at the western narratives that have galloped through pulp novels, illustration, film and the fine arts for more than a century.

"Art is not innocent," MMFA general director Nathalie Bondil said at the show's recent unveiling, and western art is less innocent than most. Much of the work on display puts a heroic stamp on the often-violent settlement of North America, and brands Indigenous peoples as savage or submissive folk who were doomed to disappear.

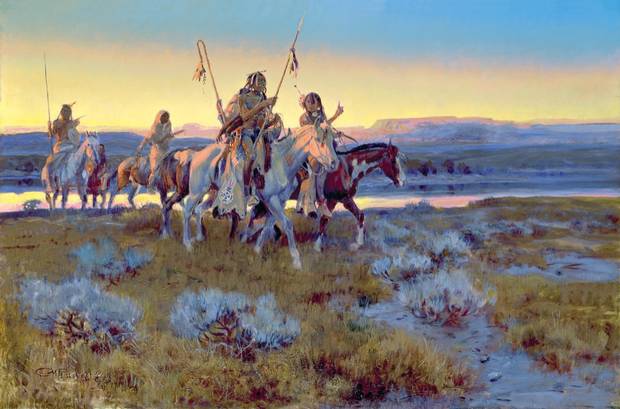

Charles Marion Russell (1864-1926), Piegans, 1918, Oil on canvas, 61 x 91.4 cm, Petrie Collection

Painters and illustrators constructed a visual mythology of the west before the invention of cinema. They emphasized the grandeur of the landscape, as a sublime panoramic void waiting to be filled.

Westerns were among the first movies made in Hollywood. Directors such as John Ford fed on the visual vocabulary provided by the likes of Frederic Remington, Charles Schreyvogel and Charles Marion Russell, who painted the Piegan (Blackfoot) riding the plains during his trips to Alberta a century ago. Many leading western artists were also illustrators, whose need to make a punchy impression on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post carried over into their paintings. Remington and Newell Convers Wyeth (father of Andrew) emphasized vigour and action, putting the spectator at the edge of a gun brawl or in front of a charging line of ponies. The latter trick is still sometimes enacted in live form by the RCMP's Musical Ride.

None of this old-time western stuff is great art. It's visualized ideology, easy to reproduce and endlessly recyclable on film. Hollywood's contribution was to animate and elaborate a few character types: the restless cowboy, the upright sheriff, the villanous rustler and the even more villainous Indian.

The show makes much of classic western films, such as Ford's Stagecoach and Fred Zinnemann's High Noon, a favourite film of several U.S. presidents. Many such films were driven by a strong man's need to avenge a wrong, usually with a bullet. One question the exhibition doesn't raise is the extent to which the gun's role as problem solver in western narratives fuelled the United States' lethal romance with firearms.

A small but important part of the show touches on the lure of the western in Quebec. As singer-comedian Patrick Groulx noted wistfully, "Life is hard for the cowboys of Quebec / a job here and there, not like in the States…" Tribute is made to Quebec-born writer and illustrator Will James (Joseph Dufault) and to singer and actor Willie Lamothe, whose first album in 1946 was called Je suis un cowboy canadien. Among the many film clips exhibited are scenes featuring well-known Quebec performers Robert Charlebois and Carole Laure.

Significant space is given to revisionist films, including Easy Rider, Little Big Man and Brokeback Mountain, in which white savagery and intolerance became a focus. The Italian westerns of Sergio Leone, as film scholar Austin Fisher writes in his catalogue essay, broke from type by exposing "an established society in decay, rather than a nascent one on the cusp of modernity." Leone looked at the frontier with the jaded eye of a man who had survived fascism and a devastating war.

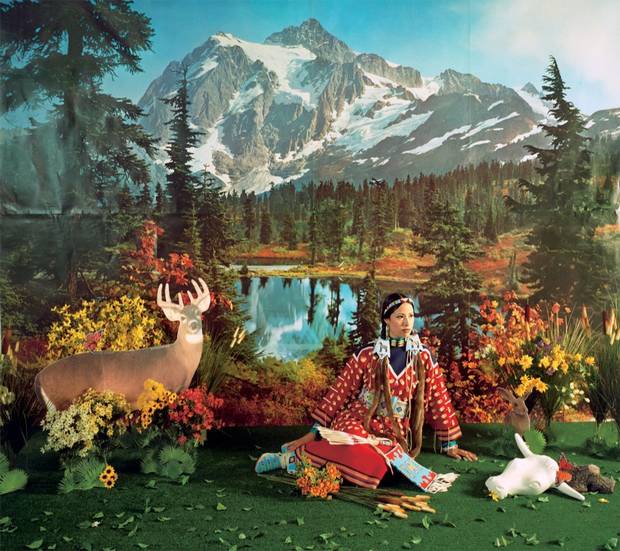

Wendy Red Star (born in 1981), Indian Summer, from the series “Four Seasons,”, 2006, chromogenic print., Collection of Brian Tschumper.

There's also a section devoted to responses to the western template by contemporary artists, including Indigenous creators. Kent Monkman sends up the grooming of the Hollywood Indian in a hilarious silent film. Wendy Red Star's self-portraits with fake landscape and "Indian" props are a modern retort to Montreal photographer William Notman's long-ago portraits of make-believe studio Indians. Fritz Scholder's Indian Power (1972) revisits James Earle Fraser's 1915 sculpture The End of the Trail – "the single most powerful icon of Indians in North America," as Thomas King writes in his book, The Inconvenient Indian. In Scholder's painting, Fraser's played-out brave sits up on his horse and raises his fist in defiance.

The exhibition was first seen at the partnering Denver Art Museum, although MMFA curator Mary-Dailey Desmarais said the Montreal version is about a third larger, with more contemporary work, and an essential gathering of beaded garments and ledger drawings from western Indigenous peoples. Desmarais guided the focus on western film, and its debt to visual art. Her attempt to claim Jackson Pollock as a western painter is less convincing, although he was born in Wyoming and styled himself as a cowboy of the art world.

Missing from the show is any mention of television's long prime-time investment in westerns, via top-rated shows such as Bonanza, starring Canadian Lorne Greene, and The Lone Ranger, with Six Nations Mohawk Jay Silverheels as Tonto. TV has also had its revisionist westerns, including Breaking Bad and Westworld.

Thomas Moran (1837-1926), The Mirage, 1879, Oil on canvas, 63.8 x 158.4 cm. Orange, Texas, Stark Museum of Art.

Tom DuBrock

It's kind of incredible that Tonto gets no space at all in this exhibition, given the tenacity of that particular stereotype. "Tonto was the Indian that North America deserved," writes Thomas King with undisguised irony, "pleasant, helpful and obsequious."

The MMFA's series of 15 film screenings includes Zacharias Kunuk's Maliglutit, the Inuit filmmaker's twist on Ford's film, The Searchers, which starred John Wayne. I doubt that Wayne would approve of Kunuk's anti-colonial revision, any more than he would have danced along with Lady Gaga.

Once Upon a Time … the Western: A New Frontier in Art and Film continues at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts through Feb. 4.