Pretty much all of us at one time or another have felt an indissoluble union with the universe. This sensation, of a seemingly boundless oneness beyond life’s quotidian rhythms, usually comes unbidden, without the aid of drugs, often in natural settings but not exclusively so.

For many, maybe even most, such moments are, well … interesting – pleasurable mysteries, nice interludes from the sheer in-your-faceness of the material world. (But, again, not exclusively so: Henry James’s dad was famously blindsided by an “insane and abject terror” – “a vastation” – while staring into a fireplace in May, 1844.) Some might even deign to call them spiritual, but not get much more descriptive than that. The moment proves fleeting. The phone buzzes. Your kids wonder if you can drive them to Dairy Queen.

For others, though, the experience is nothing less than an epiphany – an intuition or infusion of the divine in the universe and an unignorable, life-changing prod both to explore that intuition and to manifest it somehow in one’s being and the world.

Eleven years ago, Katharine Lochnan had just such a “powerful sense” of this “divine immanence and transcendence,” as she puts it, while searching and researching her Celtic roots in Ireland.

It happened on a September’s day as the veteran Art Gallery of Ontario curator stared at the Burren, the famous limestone karst landscape in County Clare. Shaken and stirred, she returned home to enroll in classes in religion, spirituality and mysticism at Regis College at the Toronto School of Theology, University of Toronto. (She’s now just five courses short of a master’s degree in theological studies.) She also took painting lessons to help put the “mystical element” into a painting she was doing based on photos from the Ireland trip.

More importantly, at least for the art-going public, Lochnan’s passion has resulted in her lead curation of a new, staggeringly ambitious sprawler of an exhibition at the AGO. Opening this weekend, Mystical Landscapes: Masterpieces from Monet, Van Gogh and More is at once a feast for the outer eye of the senses and the inner eye of the soul – more than 90 works created between 1880 and 1930 by 37 artists, mostly painters, from lenders in 14 countries, including Canada, hung (mostly) on clean white walls.

Five years in the making, it’s a joint project of the AGO, which enlisted guest Canadian curators Roald Nasgaard and Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov to assist Lochnan, and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The last will be the exhibition’s second (and final) berth after its Toronto run ends Jan. 29 next year. (Opening March 13, the Paris show will include about 16 works unavailable to the AGO and be titled Beyond Stars: The Mystical Landscape from Monet to Kandinsky.)

Lochnan, who became the AGO’s senior curator of international exhibitions in 2014 after 38 years as its curator of prints and drawings, has organized Mystical Landscapes around seven or so themes. Their titles include The Life Journey and the Mystic Way, Monet and Spiritual Enlightenment, Landscape and the Dark Night of the Soul, and The Cosmos and Mystical Experience.

I confess to being of two minds about the decision to use the prism of mysticism as the exhibition’s organizing device. I take the point that the urbanization, industrialization, materialism and aggressive nationalism of the late-19th/early-20th century provoked a spiritual crisis among artists of all stripes, some of whom sought consolation in either deep engagements with traditional religion or journeys into more esoteric, often non-Western realms. I take the point, too, that the ineffability and subjectivity of the mystical experience makes it a natural subject for the visual artist. After all, he or she trucks in symbol and metaphor, atmosphere, portent, dreams, the decisive moment frozen in time, the potency of colour. Only music is likely the better medium to convey the mystical experience, even to the point, possibly, of inducing such an event in the listener.

On the other hand, the notion of the mystical is so broad, ambiguous and slippery as to be almost too inclusive and capacious. A truly epochal art show, to my mind, has to have a kind of essential/it-could-only-be-thus quality – something Lochnan unequivocally achieved with her magisterial Turner, Whistler, Monet: Impressionist Visions exhibition of 2004-2005. Mystical Landscapes is a great show of often great beauty, accompanied by a sumptuous catalogue. But it’s dogged by the sensation that it could be the prototype for another show and another show (and another) with the same theme but a completely different cast of creators each time.

Moreover, since spirituality and mysticism (not all spiritual experiences are mystical, of course) have long informed art practice and content, is it really all that radical to argue that, for example, the melting majesty of Monet’s Rouen Cathedral: The Portal and Tour d’Albane in Sunlight (1893), included here, can be construed as an illustration of Buddhist immaterialism (“First there is a cathedral/Then there is no cathedral/Then there is,” as Donovan might have sung in 1967) as much as an embodiment of Impressionist principles? Best, I think, finally, to see the show as an extraordinary, lovingly installed collection of works connected by various affinities of theme and content (paths, groves, vistas, skies, crossroads, suns, mountains, dawns, dusks and reflections abound), without getting too hung up on it as a magical mystical tour.

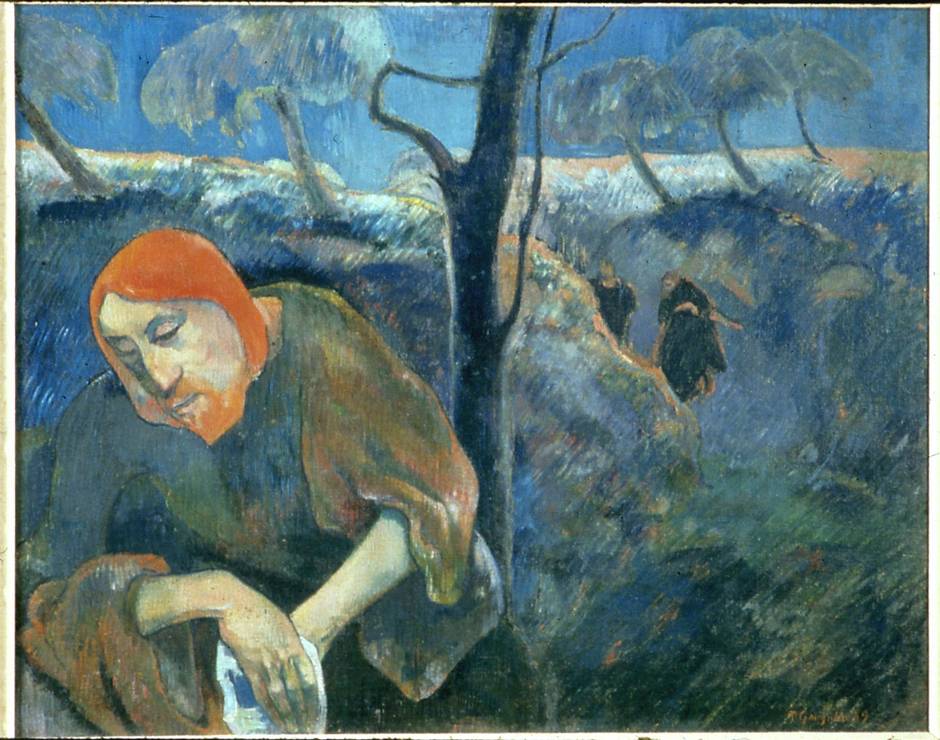

As its subtitle suggests, Mystical Landscapes is salted with big hits by big names. Besides the eight (!) Monets, there are four Gauguins, two Georgia O’Keeffes, three Arthur Doves, six Maurice Denis canvases and three van Goghs. Included among the last is one of the master’s greatest oils, Starry Night over the Rhône, lent by the d’Orsay. Finished in Arles in 1888 just two years before his death, it glistens with such freshness you’d swear van Gogh had painted it only last week. And what painting! Every bold, beautiful, luscious stroke can be seen on the canvas. Also on view: individual pieces by Piet Mondrian (a stunning apple tree/mandala), Egon Schiele (a bleak, dense Landscape with Ravens, from 1911), Edvard Munch (a psychedelic sun scene) and Ferdinand Hodler, plus a good showing from Canadians Lawren Harris, Tom Thomson, Emily Carr and Frederick Varley. (Varley’s harrowing Gas Chamber at Seaford, from 1918, is an exhibition highlight, in fact. It will be interesting to see how he and his compatriots fare with the French public and critics next year.)

Yet, for all this “celebrity,” one of the exhibition’s greatest strengths is the attention it accords lesser-known artists, or at least artists relatively unfamiliar to North American patrons. They include: France’s Charles Marie Dulac, a Franciscan lay friar who’s given his own suite here in which to display a selection of 22 near-evanescent, deeply calming lithographs and a handful of equally contemplative paintings; Fernand Khnopff, a reclusive Belgian Catholic who worked largely in grisaille to produce unpeopled scenes of great stillness; and William Degouve de Nuncques, another Belgian, whose The Pool of Blood (1894), is one concentrated nightmare of a painting.

However, for most, the real discovery is likely going to be Sweden’s Eugène Jansson (1862-1915). He’s represented by four large, fin-de-siècle works in Mystical Landscapes, three of which are absolute knockouts, equal, almost, to the best of van Gogh, Munch and Whistler. The three are very much of a piece – vast, seething voids of rich nocturnal blue, flecked with misty white, simultaneously suggesting water, sky, light and the writhing, oceanic yearnings of the human subconscious. Dare one pray for a solo Canadian exhibition sooner rather than later?

Not all the unknowns, utter or relative, are as rewarding, of course. Wenzel Hablik’s Crystal Castle at Sea (1914) may be a national treasure at its home in Prague’s National Gallery. Here, though, in the last, darkened space of the AGO show, it’s more kitsch than cosmic, the kind of art you imagine in the cafeteria of the original Starship Enterprise. The same goes for G.F. Watts’s The Sower of the Systems (1902), positioned near the Hablik. Its depiction of God hurling the cosmos into existence might have wowed ’em in Edwardian England – but today He looks like the inspiration for the “hairy thunderer” in Deteriorata, that satirical spoken-word hit of the early 1970s. Marvel Comics fans likely will think “Galatacus” or “Silver Surfer.”

Such flubs are, of course, inevitable in a showcase as big and ambitious as Mystical Landscapes. The AGO should be applauded for again stretching its sinews, as it did earlier this year with Outsiders: American Photography and Film, 1950s-1980s, to originate an international-calibre exhibition.

Mystical Landscapes: Masterpieces from Monet, Van Gogh and More opens Saturday at Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario for a run through Jan. 29 (ago.net).