Some time early in the last century, the ridiculously influential Marcel Duchamp coined the phrase “retinal pleasure” as his put-down of works of art that enchant primarily as visual entertainments. He thought they were facile.

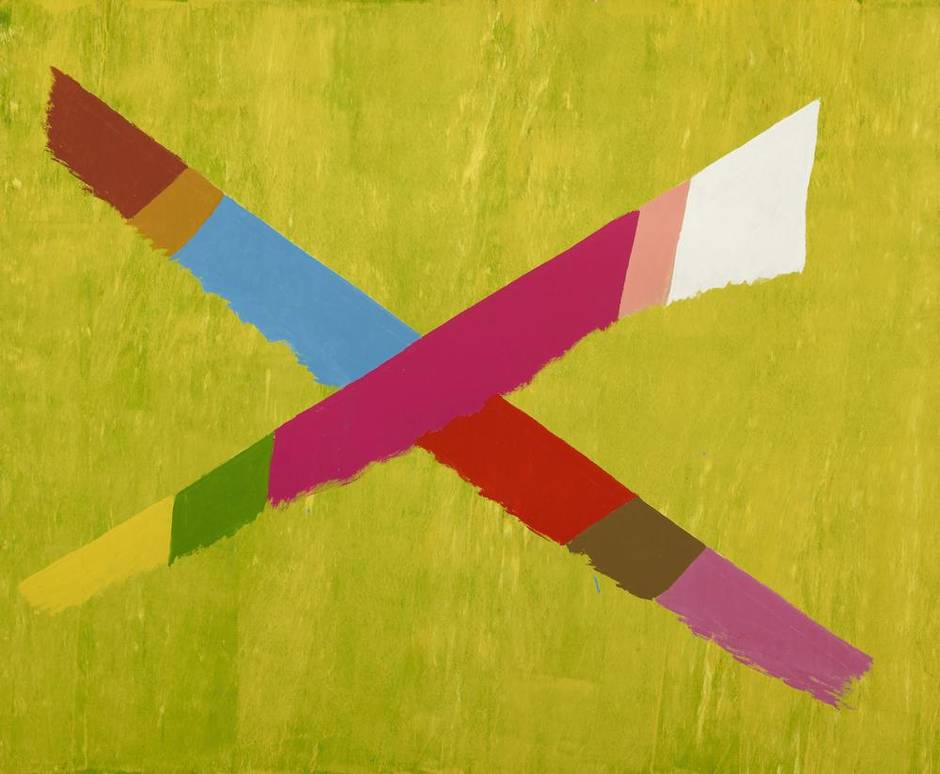

Too bad he’s not alive today and within travelling distance of Ottawa, because I think even his cold eye would be warmed, stimulated even, by the treasures and pleasures of the Jack Bush retrospective that has just opened here at the National Gallery of Canada. Featuring some 130 works, mostly big paintings culled from private and public collections in Canada and the United States, it’s a celebration of colour as form, colour as a field, colour as life-force, colour as therapy, colour as exaltation, colour as colour. And it’s a deeply satisfying exploration of delights and audacities that can occur when colour is applied to a flat surface via the miraculous medium we call paint.

In a 1968 entry in the daily diaries he kept for 25 years until his death (too soon) at 68 in 1977, Bush wrote of his desire to “come up with a show that goes pow! pow! pow!” This is that show.

And how lucky Ottawa is to have such a tonic of tonality for the next three months, as much of Canada girds itself for the blustery, grey, overcast and cold weather ahead. Would that there was a federally subsidized program to fly in the residents of snow-bound Saskatoon or rainy Victoria or fog-wreathed Halifax to bask in this show’s glow for a day or an afternoon.

Co-curated with finesse and drama by Toronto-based Bush expert Sarah Stanners and Marc Mayer, NGC’s director since 2009, this is the first Bush retrospective to occur in almost 40 years – “high time,” in other words, “for a monographic, mid-century Canadian show of painting,” as Stanners put it the other day.

The exhibition spans Bush’s total career. Along with the expected highlights from his 1963-77 heyday, there are little-seen or never-before-seen gems – a generous sampling from his many years as a highly accomplished commercial illustrator in Toronto, some of his early forays into serious painting in the 1930s, inspired by the likes of the Group of Seven, Thomas Eakins and Thomas Hart Benton, and a suite of five brushy flower paintings from 1960.

You’ll also find a vitrine containing the journals in which Bush meticulously recorded his painting activities, a process that produced more than 1,600 works by the time he died of a heart attack in a Toronto hospital. These journals have been the ur-document for the Bush catalogue raisonné Stanners has spent the last three-and-a-half years preparing, with the aim of publishing a four-volume boxed set by fall 2016.

One of the retrospective’s great blessings is the lack of art-world cant in its didactics – an entirely intentional omission. Stanners remarked: “People have said, ‘Oh, you have to have a theory, an idea, a curatorial nut throughout the whole show.’ But what I actually want is for the paintings to be primary here. I want people to stand in front of the paintings and feel them, the visceral effect. We don’t get an opportunity to stand in a body of an artist’s work too much today. Often, the museum experience is encyclopedic – there’s this masterwork from each period going along. But this exhibition allows you to immerse yourself in the particular periods of the artist.”

Another blessing is its refusal to re-fight the culture war that dogged Bush for most of his mature career. Lest we forget, the Camels-smoking, jazz-loving, martini-drinking Bush was determined to “play in the major leagues” of world art, to “go out and try to beat Matisse,” as he told The Globe and Mail in 1976. Back then, major-league painters, almost to a man (Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, Robert Motherwell) and woman (Helen Frankenthaler), were based in New York. It was home, too, to the era’s most influential critic, Clement Greenberg, who’d famously championed Jackson Pollock and the first wave of abstract expressionists.

Greenberg and Bush took a shine to each other pretty much from their first meeting in Toronto in the summer of 1957, and remained friends from thereon. Never averse to giving advice or opinions, Greenberg came to be seen by some Canadian curators, collectors and critics as “the art director of Jack Bush Studios,” in Mayer’s formulation, and more generally as the “doctrinaire imperialist dictating rigid and formalistic theories to Canadian artists” who, for all their “provincialism,” might “otherwise have developed in a more independent way.” (Robert Fulford, 1993.)

Greenberg is a presence in the retrospective – but more as “sounding-board” than Svengali, and just one of several individuals, including Bush’s wife, Mabel, and his psychotherapist, J. Allan Walters, who, in Mayer’s estimation, helped “Jack Bush become Jack Bush.” Today, said Mayer, “we’ve kind of healed from those culture wars. Now it’s like, ‘Why weren’t we supposed to like those paintings again?’” Or as a younger-generation scholar such as Stanners puts it, “I don’t care about the polemics; I care about the artwork.”

Certainly there’s much to care about and ponder here: The artist’s equipoise of economy and sophistication; the unabashed virility of the canvases (all those thrusts and bars and totems and firm colours), but minus the tight-jeaned, proletarian machismo of Pollock or existential heaviness of Jean-Paul Riopelle.

Then there’s the rightness and the surprises of his evolution – the way, for example, he would carry over a motif (an asteroid-like splotch, a swoosh, a portal-like shape) from period to period; his refusal to settle on shtick; the Matissean lyricism of such late paintings as Basie Blues from 1975 and the 1977 acrylic Chopsticks; the Everyman nature of his life (dutiful dad to three sons, devoted husband, mortgage-paying suburbanite, well-groomed dresser); and the genius of the art.

Above all, there’s the freshness of the work. Speaking at the NGC the other day, Stanners told of the pleasure and uplift a Bush painting has provided one long-time owner. “It’s never let me down,” was how the owner put it. Once you’ve seen the sumptuous show, you’ll know just what she was talking about.

Jack Bush is at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa now through Feb. 22, 2015. It is next scheduled to appear May through August, 2015, at the Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton.