In this era of branding it's easy to think of a person as a product. Spending a day recently with Vicki Simons Heyman, wife of Bruce Heyman, U.S. ambassador to Canada, I couldn't help but imagine her as some fizzy drink. Something a bottler might call Mrs. Vicki's Excellent Elixir of Effervescence.

She's bubbly, in other words. "Engaged." Energetic. "A great believer in the possible and the positive" with an especially "deep feeling" for the visual arts and why those in the country's seats of power should talk, dissect and celebrate culture in all its forms. (Each lover of the arts has "their particular sense," she says. "Mine's dominated by the visual.") And in just two quick years, Heyman has used that keen artistic sense in an unprecedented effort to promote visual arts from one of the most powerful, if unexpected, perches in the country.

Heyman likes to describe herself as a "very much the glass-is-half-full person," her voice graced every now and then by a drawled vowel betraying earlier times in Kentucky and Tennessee. Quick to laugh, even quicker with a high-wattage smiley smile, if she were to declare, say, "I embrace the audacity of hope," you wouldn't be surprised.

After all, Heyman, 58, and her husband, 57, were among the first serious endorsers of Barack Obama back in 2007 when the then-junior U.S. senator from Illinois stunned the world by announcing he would try to be the Democrats' standard-bearer in the 2008 presidential election. By the time Obama won his second term, in 2012, the Chicago-based Heymans had raised more than $1.7-million (U.S.) on his behalf.

In September of 2013, Obama declared he’d be naming Bruce Heyman the 30th U.S. ambassador to Canada. In March, 2014, a little more than two weeks after being confirmed to the post by the U.S. Senate, the veteran Goldman Sachs executive and Vicki, his wife of now 35 years, were moving into Lornado, a 32-room pile of limestone bricks near 24 Sussex Dr. and Rideau Hall, its manicured four hectares offering sweeping views of the Ottawa River. Built in 1907 by a local industrialist, it was bought by the U.S. State Department in the mid-1930s. (The manor’s name is a contraction of sorts of Lorna Doone, the 1869 romance novel by R.D. Blackmore that purportedly was a favourite of Lornado’s first owner.)

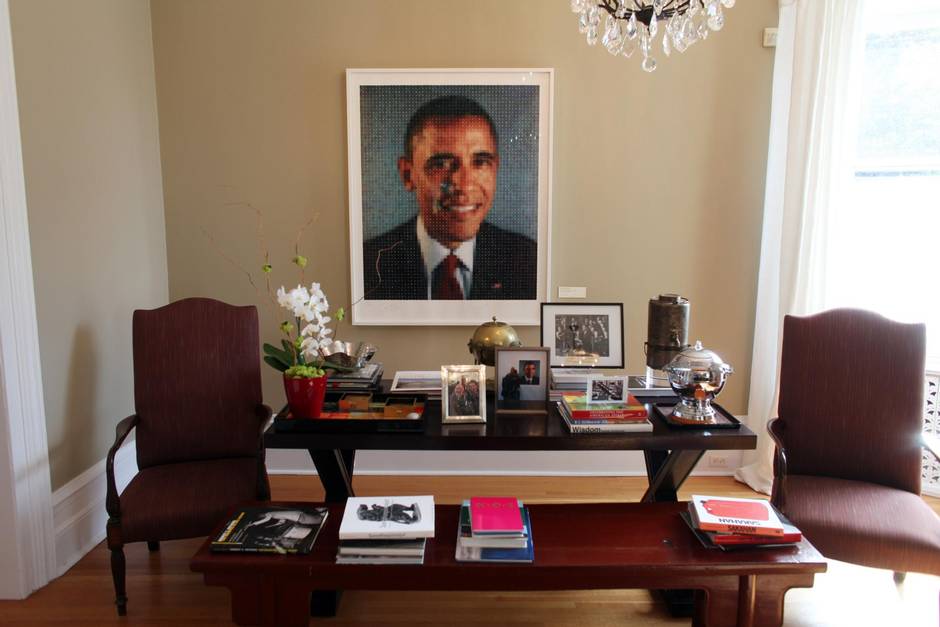

Vicki Heyman doesn’t disavow the ambassadorship is a political appointment for services rendered to what she calls “our Obama family.” Indeed, a 141-cm-by-112-cm Chuck Close watercolour pigment print of the president, owned by the Heymans, looms large over Lornado’s main-floor library. But she’s just as quick to insist Canada was their first (and second and third) choice when they were asked to list their preferred destinations. Moreover, they were not entirely unaware of Canada on March 26, 2014, the day Heyman was sworn in as ambassador.

His portfolio as Goldman Sachs’ managing director of private wealth management had covered some 13 states and half of Canada while Vicki, though born in Cincinnati and raised in Ashland, Ky., had paternal great grandparents, Samuel and Tybae Simons, who left Belarus in the late 19th century to settle, eventually, in Toronto. Four of their six children, in fact, would remain in Toronto but in the early 1920s, Heyman’s grandfather, Charles, and her uncle, Jack, left for Cincinnati to open a barber shop. Vicki Heyman’s father, Robert, born in 1927, later became owner and manager of Star’s Fashion World, at one time Ashland’s largest clothing retailer.

The Obama portrait is one of numerous artworks found on Lornado’s spacious ground floor, several of which were, like the Close, brought from the Heymans’ Chicago home. Most are by U.S. artists, of course, including a real Campbell’s tomato soup can label autographed by Andy Warhol hanging framed in the guest bathroom.

Recently, though, the Heymans were lent Colorado River Delta, Mexico, a large colour photograph by Toronto’s Edward Burtynsky. The first Canadian work admitted to Lornado during the Heymans’ stay, it currently hangs in the living room near the entrance to the sunroom where you can see a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle of a Lawren Harris painting of Mt. Lefroy that the ambassador has been poking away at for months. There are also two works of the same subject, a tumbling woman, one done in watercolour, the other a glass sculpture, both created by Eric Fischl, who, though New York-based, spent several crucial years in the 1970s teaching and painting at what is now the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design.

The art isn’t just for show. The Heymans have considered themselves teammates pretty much from the days they courted and sparked at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University in the mid-seventies, and it’s an ethos the self-described “best friends” have brought to the 18 months of what some call their “co-ambassadorship.”

By many accounts, Bruce Heyman’s tenure in Ottawa hasn’t been an easy one, plagued by seemingly intractable stresses and strains between the Obama and Harper administrations, not least being delays over the proposed Keystone XL pipeline. The couple, nevertheless, has avidly embraced the country, travelling hither and thither – a recent trip to St. John’s and Fogo Island means they now can claim to have visited every province – networking up a storm while becoming known for throwing a fine party, indoors and out, at Lornado. They’ve also enrolled in a French class run by the State Department.

Avid as ever to be more activist than observer, Vicki Heyman’s role in the co-ambassadorship has been that of “cultural envoy” – a “connector” and a “uniter” keen to facilitate “big-tent, open-arms dialogues … on issues of borderless import.” Art for Heyman isn’t “fluffy stuff.” Which is why, in part, Ambassador Heyman’s first two major public speeches in Ottawa were delivered at, respectively, the National Gallery of Canada and the National Arts Centre in June last year. Which is why virtually all the art in her Ottawa home has “a social driver to it … art that can come off the walls and be a part of a conversation” involving “the academic sphere, the art sphere, the entrepreneurship sphere.”

Take the Fischls. Striking as they are in and of themselves, the poignant painting and the glass maquette also are serving as a promotion of sorts for a free “conversation” occurring Sept. 10 between their creator and National Gallery director Marc Mayer on stage at the NGC auditorium. It’s the third such “contemporary conversation” this year organized by the gallery, the U.S. Embassy and the Art in Embassies program that’s been run by the State Department since 1963. The fourth and final conversation, featuring U.S. photographer Stephen Wilkes, is set for Nov. 19; the first two, involving mixed-media artists Marie Watt of Portland and Chicago’s Nick Cave, were held respectively in February and May. Like Fischl, Wilkes, Cave and Watt all have art exhibited at the ambassador’s residence.

The series has been a great success. Indeed, all 399 seats for the Fischl event were spoken for mere days after the date for the conversation was announced. Currently there’s a waiting list of more than 390. Spiking the interest is that Fischl’s original inspiration for his iterations of Tumbling Woman were the victims of New York’s World Trade Center disaster 14 years ago this month.

In addition, the NGC has just installed on its premises a life-sized translucent acrylic cast of Tumbling Woman for display until Sept. 14 whereupon it will be moved to the U.S. Embassy for exhibition until Oct. 23. Fischl’s also participating in a smaller, more intimate, invitation-only event Sept. 9 at the Canada Council Art Bank. Its focus is on painting, the medium that first brought Fischl to international attention in the early 1980s, and will feature a panel discussion involving six rising Canadian painting stars including Melanie Authier and Jessica Bell.

During my visit to Lornado, Heyman hosted a meeting there for the Sept. 9 panel involving, among others, three of the participating artists and Ming Tiampo, a Carleton University art history and curatorial studies professor who, for the Heymans’ tenure, has helped staff to organize a series of visual arts “salons” at Lornado – small, orchestrated events with no more than 40 attendees, the art in Lornado serving as touchstones for discussing issues related to race, culture, migration and identity.

Following that meeting, Heyman, her executive assistant, me, a photographer, a cultural liaison officer and two representatives from the U.S. Embassy’s Office of Public Affairs piled into an SUV to travel to downtown Ottawa. Our destination was HUB Ottawa, an electronic “coworking community” Heyman likes to champion in her role as a booster of social innovation and education. The plan was to meet with Tony Hayton, former horticulturalist and fuel conservation expert, who also happens to be an enthusiastic collector of paintings by the Florida Highwaymen.

Never heard of them? You will if Heyman gets her way.

She knows that, as political appointees of a president in the twilight of his second term, she and her husband have maybe 18 or 19 months left in their great Canadian adventure. And one of the things she’s hoping to accomplish, preferably in time for Black History Month next February, is an exhibition here of the Highwaymen, a group of 26 African-American artists, largely self-taught, who began painting folky Florida scenes in the mid-1950s, selling the works (now estimated to number anywhere from 100,000 to 300,000) out of the trunks of their cars as they drove up and down U.S. Route No. 1. Not just an exhibition, mind you, but a celebration of Florida “soul food” (cue the State Department’s “culinary diplomacy” budget) and live music, plus symposiums.

Later, over lunch, Heyman expressed her belief that “the cross-cultural connections” she’s been working on will continue and amplify after she and her husband return stateside. “There’s no way to keep a good woman down,” she laughed. In the meantime, “[we’re] living in the moment, flowing with the river.”